Summary

The rapid development of innovative building materials and technologies—and the variety of the options—requires a common framework to help construction stakeholders evaluate efficiency, energy, and lifecycle savings. Evaluation of these new and emerging materials and technologies has become critical for both public- and private-sector actors seeking to improve building construction. We propose an evaluation framework to assess the technological, market, and financial viability of new and emerging buildingproducts. Our framework is based on:

(1) technological criteria (manufacturing energy use, emissions reduction, technology development stage, other material or product technical parameters);

(2) market criteria (market size, scalability); and

(3) financial criteria (cost of novel technology implementation compared to business-as-usual or BAU).

Who Will Use the Proposed Framework?

The primary audiences for the proposed evaluation framework and criteria are:

(1) investors who want to understand their return on investment in start-ups as products commercialize. |

(2) novel technology manufacturers, who need to understand marketplace needs and develop information to help end users choose the right product. |

(3) policymakers. |

(4) public and private procurement officials who need to evaluate selections on a consistent basis, especially for infrastructure and other large projects. |

Additionally, the architectural and engineering (A&E) communities, who may be considering the use of new or emerging technologies in projects, may find it useful to better understand these technologies.

Why Do We Need a Building Technology Evaluation Framework?

Over the past 5-10 years there has been an explosion of new and emerging building material technologies and products that have been funded, rapidly developed, and introduced in the construction market. Energy use and emissions are associated with the manufacture of building products, and the construction process itself. Reductions in energy and emissions may occur during raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and installation; they also occur during product use stages and end-of-life disposal or recycling (see our embodied carbon landing page for more information). Innovative technologies emerge from university research and national labs, startup companies, and established manufacturing companies’ research and development (R&D) departments. Technologies in earlier R&D stages are referred to as “emerging,” with those in later deployment stages called “new” given their limited use in the market. Collectively, these technologies utilize a wide range of strategies to improve material, energy, product, and process efficiency, including using alternate raw materials, alternate process heat, additive i.e., strengthening materials, and other approaches (DC2 2024).

The uptake of new and emerging building technologies has been slow for several reasons, including:

- lack of understanding and measurement of their efficiency potential, and in some cases, market/end-users’ inability to fully understand actual performance and savings in real-world field applications;

- lack of cost parity with traditional products;

- lack of distribution channels (e.g., for concrete, through ready mix companies);

- limited understanding of how to use new products and of how they meet construction and building codes and standards; or

- inadequate or incomplete product technical specifications and questions about their scalability, longer-term durability, performance, and optimal use applications (NETL 2023), leading to risk aversion to using new products in a traditional industry.

These barriers to adoption lead builders to default to previously used, known options, especially in the context of tight construction schedules and budgets.

Both public procurement and private investors are looking for opportunities to improve construction cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and timelines—innovative technologies could help achieve all of the above. Thus, all stakeholders who influence building design, construction, and material use need to better understand these new products, their use cases, and what constitutes improvements in the construction process.

Currently, environmental product declarations (EPDs)—standardized reporting labels—are used to communicate a product’s environmental impact using data from a lifecycle assessment or LCA (ISO 2006a, 2006b, 2006c—see Background) which could be used to inform the expected energy use and efficiency gains from a material or product, However, newer, more innovative materials and technologies lack EPDs because one full production year of data is required; this data can only be gathered if there’s sufficient market demand for the material or technology in the first place. Furthermore, LCAs alone might not capture the definitive emission intensities or savings provided by products that use multiple materials in various quantities. Finally, there is no consistent framework for the market to assess and compare the wide range of innovative technologies across a consistent set of parameters.

Most industry trade associations and standards organizations also do not want to be perceived as choosing between new and emerging technologies or disrupting the use of traditional technologies currently dominating the market without commercially available and viable alternatives (e.g., newer options that comply with existing specifications and standards or are available at scale).

Solution to the Problem: Evaluation Framework

We propose an evaluation framework with specific criteria to assess new and emerging building technologies across a range of characteristics (see Background for more information on how we developed this framework). This system includes:

(1) Technological criteria (e.g., manufacturing energy use, emissions reduction potential, technology readiness level (TRL), and material or product technical parameters related to performance—strength and durability);

(2) Market criteria (e.g., market size, product scalability, application type, value proposition, market or product differentiation); and

(3) Financial criteria (e.g., cost of novel technology implementation compared to business-as-usual or BAU).

Within the suite of available criteria we focus on a select list of key or primary ones under each assessment category, as “threshold” or “must have” elements that need to be evaluated for all new and emerging technologies (see table 1). A particular technology may score well across multiple criteria but be missing one or more of these critical elements, without which it will fail to progress in the marketplace. We use pre-defined, three-point scales to assess criteria, using an equal weighting approach. Users of this framework can adjust the criteria weighting factors based on their needs. For example, procurement officials may prioritize financial criteria, R&D funders may prioritize emissions reduction potential and the technology development stage, while investors may focus more on the market size and product scalability. Additionally, secondary and tertiary evaluation criteria may be developed for specific materials or products to assess other attributes (e.g., material performance characteristics like strength or durability) based on priorityneeds to further expand the framework.

Table 1. Framework primary* evaluation criteria.

-

Explanation of Technological Criteria, Market Criteria, Financial Criteria

Explanation of Technological Criteria

T1 Energy and Emissions Reduction Potential (ERP) is defined as the reduction in emissions from the material or technology, its manufacturing energy (thermal/electrical energy used in a process, i.e., renewables/clean energy to lower emissions or reduce energy use), and to some extent the value proposition for an innovative technology (e.g., the additionality it offers—such as recycled raw materials—to the range of existing products in use). Users of this framework may also choose to include reduction of other air emissions to improve public health under this criterion. ERP is measured as a percent reduction compared to the BAU scenario in CO2-eq/unit.

If a product-specific EPD exists, the reported emissions (which include primary energy demand) serve as an estimate of the product ERP and could be validated. One drawback is potential data gaps in the lifecycle inventories of commercially available lifecycle assessment (LCA) tools (Esram and Hu 2021). In the absence of an EPD (product, facility, or industry average), an LCA could be conducted to estimate emissions reduced or avoided compared to BAU. Additionally, groups like NEU—an ACI Center of Excellence focused on innovative concrete technologies—provide third-party validation and verification of environmental claims for these materials and products (NEU 2024).

T2 Technology Development Stage (TDS) evaluates how close a product or technology is to commercialization based on information from the company or independent assessments of the technology by experts. TDS corresponds closely to the Department of Energy’s (DOE) TRL schema (see Background).

Explanation of Market Criteria

Information to assess these criteria would be provided by the company and would meet the DOE Adoption Readiness Level (ARL) scheme (see Background). The transition from lab bench scale to commercial production is critical in ensuring an innovative technology is market ready.

M1 Market Size refers to the potential demand for a product based on product type or percent of market share. This criterion is evaluated based on company information or a market segmentation analysis by an independent market research firm. Detailed segmentation analysis based on application type (e.g., infrastructure versus buildings, performance requirements) or even product differentiation (e.g., regionality) enables nuanced assessments.

M2 Product Scalability refers to how close the technology is to producing real-world quantities (e.g., tonnage), and whether the innovative technology process can be scaled to produce the required volume needed by the market. If the technology cannot produce real-world quantities of material while retaining product technical and performance specifications, then its market acceptance and viability diminishes. Furthermore, scalability may also be based on known availability of raw material resources and production infrastructure.

Explanation of Financial Criteria

F1 Delivered Cost is the cost of implementing the innovative technology, which must generally be less than or equivalent to the BAU technology in order to increase its economic value proposition/business case. This element is evaluated by the percent savings compared to BAU $/unit of product. In some cases, the delivered cost of an innovative technology is higher than BAU—negative savings are levelized to zero for a score of 1 within this criterion. Information to assess this element could be obtained from the manufacturer or through construction cost estimation.

This factor is especially important when it comes to a building material that operates on very low profit margins. Alternatively, the cost premium associated with new technologies will need to be subsidized to motivate the market to adopt the innovative product. Otherwise, the construction industry—with its tight budgets and timelines—will usually resort to the older materials it is most familiar with.

Evaluation and Scoring Approach

The scores across each evaluation category are combined to form a total score, revealing technological viability (based on currently available information) on a sliding scale from 1 to 15 where scores of 1-5 correspond to the lower end of the viability scale, 6-10 correspond to a mid-range viability, and 11-15 correspond to the higher end of the viability scale. Additionally, this evaluation only presents a snapshot of the current technology and investment landscape, which is anticipated to evolve over time. To illustrate how the criteria are applied, see our concrete technologies heat map and case studies.

The most promising technologies would offer great lifecycle savings at high TRLs with strong market characteristics at lower or equivalent cost to BAU. However, in some instances, an innovative material or product may only be available in smaller quantities (especially in lower TRLs) for use in limited applications within a given project despite excellent technical attributes. Thus, the architect or designer would need to decide how to use the innovative material or product while meeting their project’s cost-benefit requirements.

Evaluation Framework Applied to New and Emerging Concrete Technologies

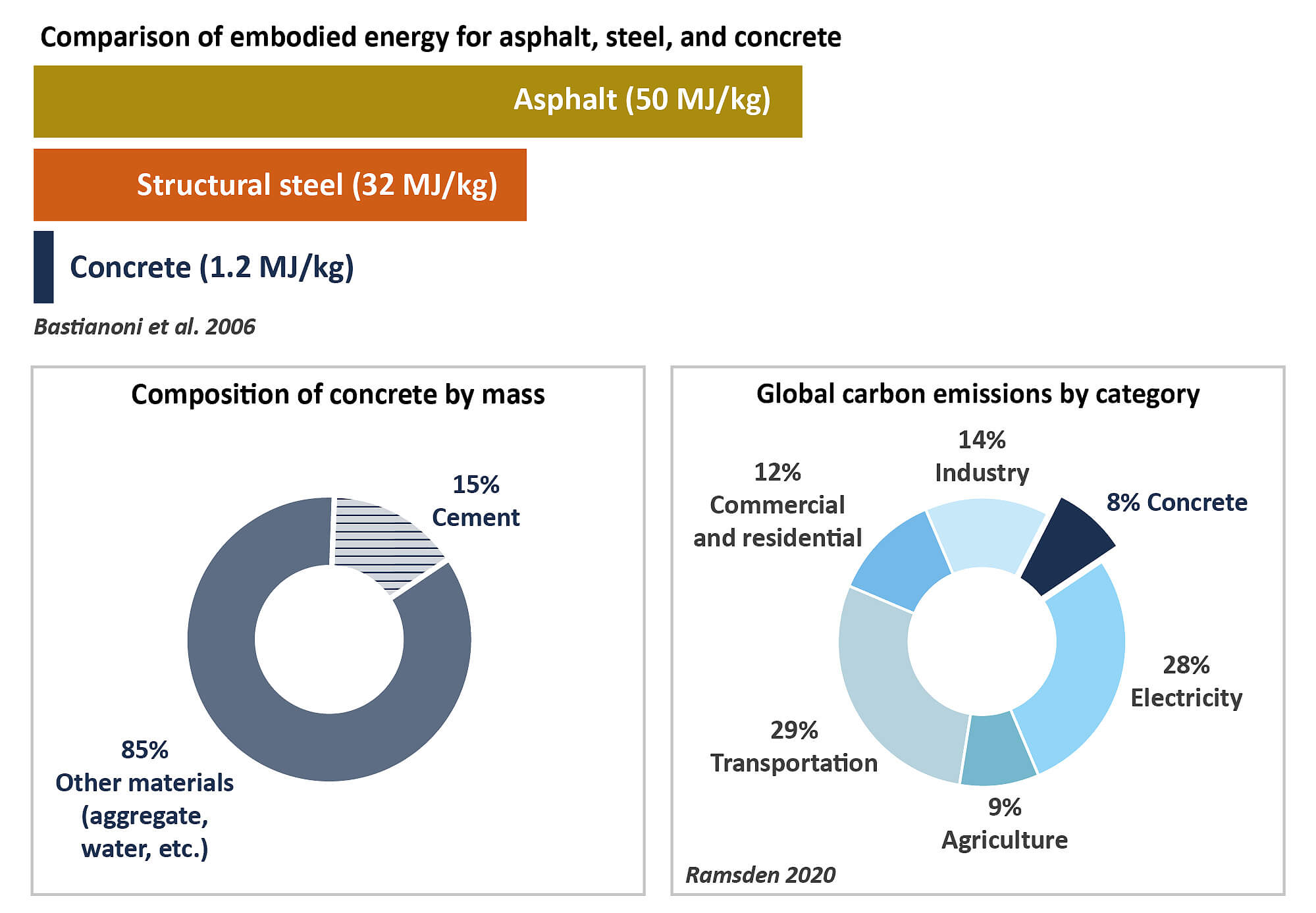

Concrete by itself has relatively low embodied energy (1.2 MJ/kg) compared to structural steel (32 MJ/kg) and asphalt (50 MJ/kg) (Bastianoni et al. 2006), with most of its emissions arising from the approximately 15% of cement (by mass) used as the binding agent in a concrete mix (see figure 1). It is the large quantity of concrete used in construction that can provide an opportunity for savings from material or process efficiency.

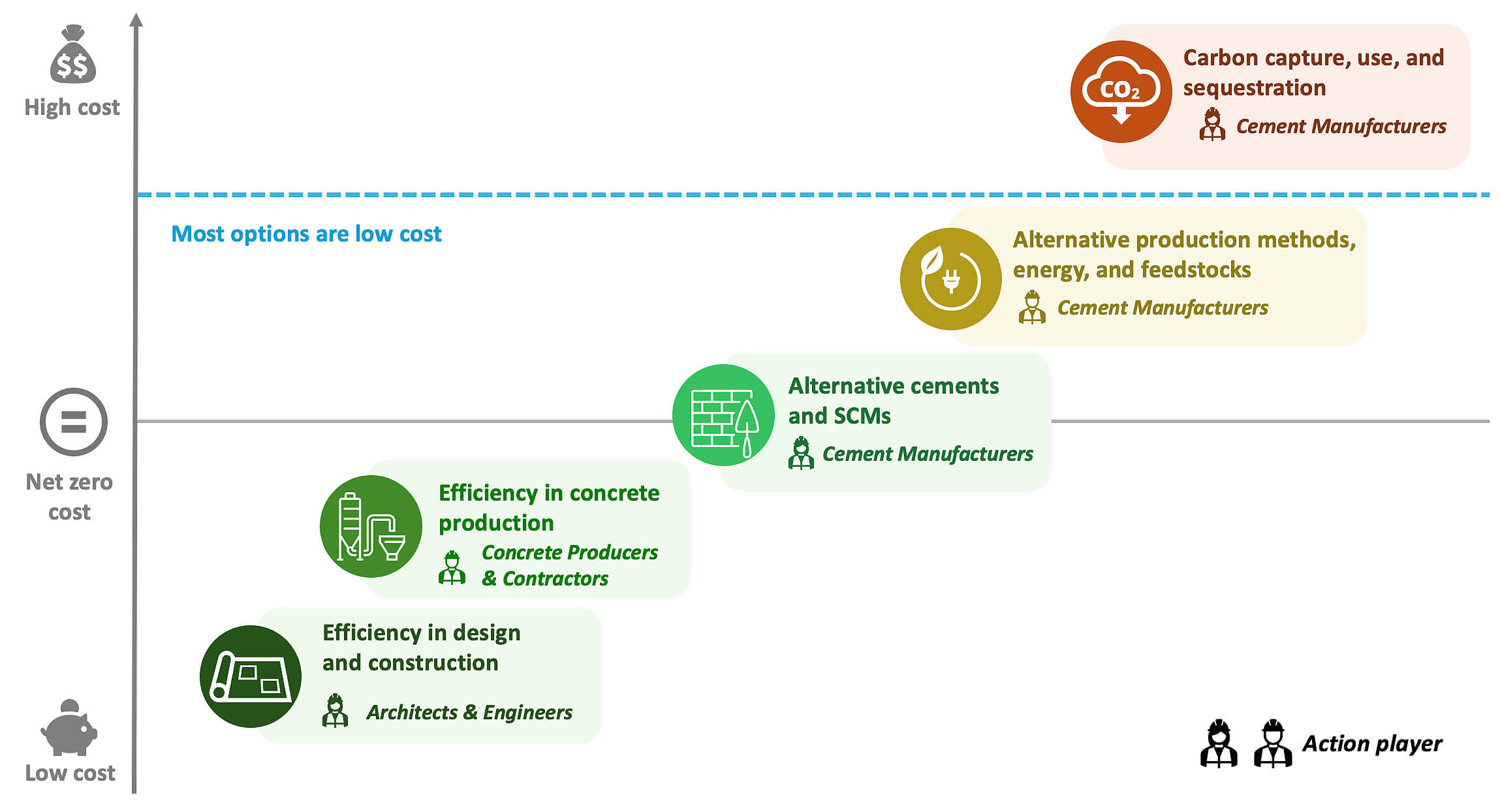

Thus, efficiency strategies for concrete need to consider all lifecycle stages, contributing components, and the whole value chain. Figure 2 summarizes the five main strategies that three different groups of stakeholders could use to improve construction efficiency from concrete, with descriptions below. There are over 100 new and emerging technology companies in operation globally that employ one or more of the below measures, about 70 of which have products or technology solutions available in the U.S. (personal communication, NEU 2025). A combined approach has the potential to drastically improve concrete products and requires collaboration among different value chain players.

-

Efficiency Strategies

Efficiency in design and construction uses concrete more efficiently in construction (e.g., by avoiding overdesign, large spans, tall buildings). Builders could also use 3D printed concrete structures to reduce build times, although this technology is niche and mainly used for disaster relief. The A&E community and developers are the key stakeholders for this strategy.

Material efficiency in concrete production reduces cement content in concrete by using admixtures, aggregate grading, or other materials. This can also include the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to optimize concrete mix designs. Concrete producers and contractors are the key stakeholders to leverage this strategy.

Cement manufacturers, including emerging technology startups are key stakeholders to use the following three strategies:

Alternative cements and replacing clinker with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs): Clinker is the key ingredient in traditional portland cement and its calcination process and high temperatures require a lot of energy to fuel the production process (GCCA 2022; Olsson, Miller, and Alexander 2023). Clinker substitution is a strategy in which SCMs—like industrial byproducts, ground glass, or other natural pozzolans—are used to replace a portion of clinker in portland cement, thereby reducing energy use. SCMs can also be used to produce blended cements—like limestone calcined clay cement. Alternative cements can completely replace portland cement binder and are not currently covered by specifications.

Alternative production methods, energy, and feedstocks: This strategy reduces energy and/or emissions by using alternative feedstocks (i.e., raw materials) and alternative methods and/or energy sources for manufacturing. For example, a company uses an alternative production/energy technology, namely an electrolytic reactor powered by renewable energy, to extract cement from an alternative feedstock. Another company may use an electrochemical approach to replace the traditional fossil fuel-powered high temperature kiln with a metal vat powered by electricity at room temperature. Examples of alternative feedstocks are non-carbonated silicate rocks or mine tailings, aggregate, and activators to make less energy-intensive concrete.

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Sequestration (CCUS): Companies capture carbon dioxide (CO2) at the cement plant or from the atmosphere to permanently sequester it within cement/concrete products (known as carbon mineralization) to improve their properties. There are variations of CCUS technologies used by different companies. For example, some technologies inject CO2into ready mix concrete where it converts to a mineral and improves compressive strength. Traditional cement could also be replaced with a calcium-rich alternative binder that chemically reacts with captured CO2, strengthening the concrete while storing CO2.

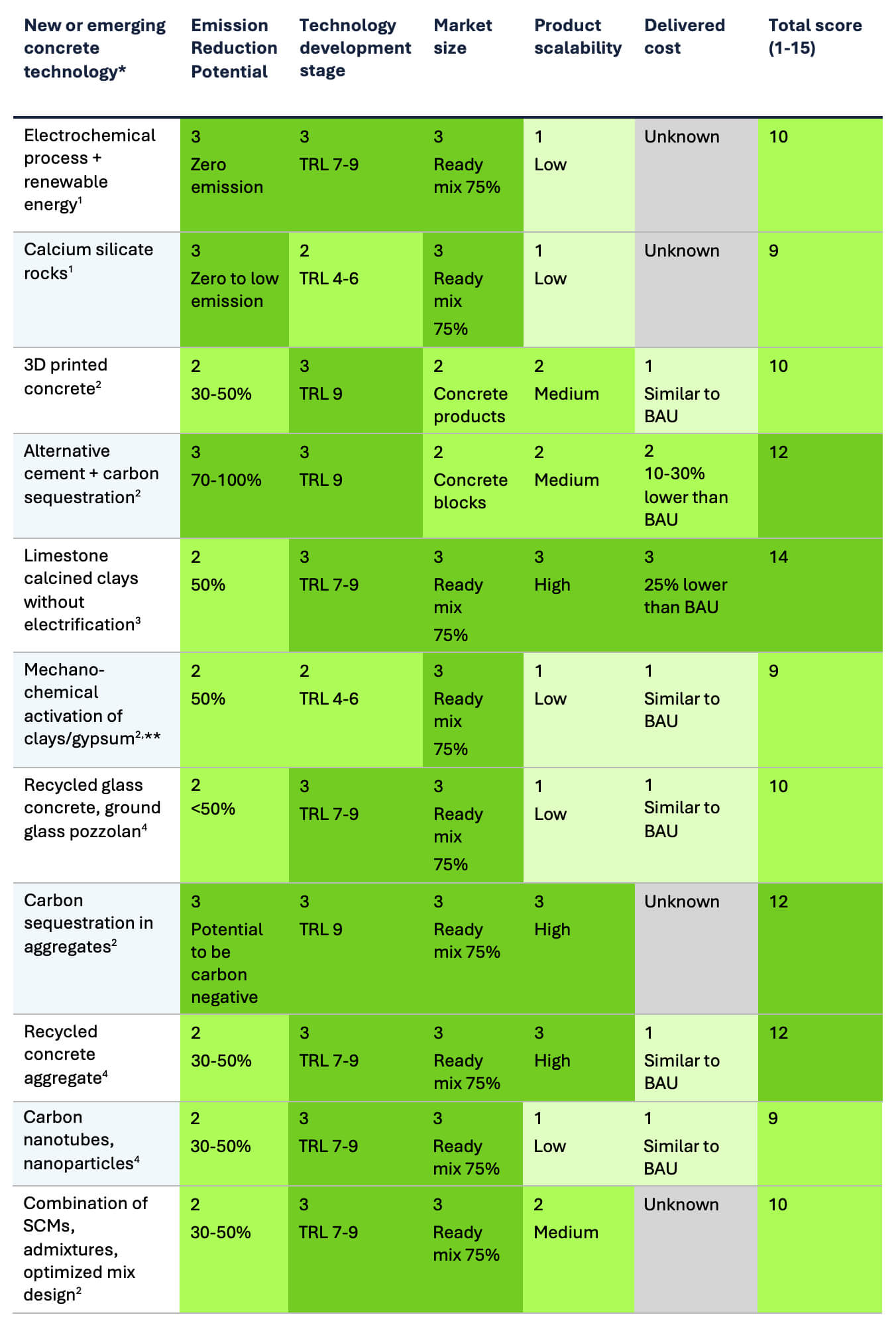

Concrete Technologies Heat Map and Rating Score

Table 2 represents a heat map evaluating a variety of new and emerging concrete building technologies at this point in time, using our proposed primary or threshold criteria that are equally weighted. The evaluation criteria applied to concrete technologies follow the scoring as in table 1. [Note: M1 Market Size is specifically assigned based on concrete product type: 1 = smaller markets, other/miscellaneous users (0-5% of the market); 2 = medium (5-25% of market) i.e., concrete products such as precast, pre-stressed, reinforced concrete, etc. making up 11% of U.S. market; and 3 = large (>25% of market) i.e., ready mix concrete which makes up 70-75% of U.S. market]. BAU comparison refers to concrete made with portland cement and processes associated with its production and/or use.

This table illustrates our methodology with a screening evaluation and is not meant to compare technologies; a full evaluation will require additional information from technology developers or vendors. Organizations such as NEU are compiling a comprehensive list of new and emerging technologies available in the market.

Below the heat map, we present brief case studies of strong candidate technologies to show how they meet our evaluation criteria.

Table 2. Heat map and score evaluating new and emerging concrete building technologies

**Also a lab technology. Source: personal communication, national laboratory 2023.

Superscript numbers indicate the number of companies whose information was used to evaluate the score which used the median across the available information.

Contact Pavitra Srinivasan or Fikayo Omotesho to add or update your technology’s score on the heatmap.

-

Limestone Calcined Clay (LCC)

Limestone calcined clay (LCC) offers wide scalability as an SCM for use in both cement (to displace clinker) and in concrete (as a blended cement) (Hasanbeigi et al. 2024). It is based on a mix of ground limestone and clay that is calcined at half the temperature of clinker, resulting in substantial energy savings. Additionally, clays are a non-carbonated material, and the ground limestone is merely ground not calcined as in traditional portland cement production, thus LCC can offer a 50% reduction in emissions. In the U.S. it is considered a TRL 7-8 technology with new plants anticipated at scale. It offers similar performance and mechanical characteristics as portland cement, especially in the long term (durability, strength), for buildings and infrastructure. For example, LCC can be used in ready mix concrete for highways, which are largely funded by federal, state, and local governments. LCC offers at least a 25% cost savings for energy and raw materials compared to portland cement. Additionally, emissions could be reduced if the clays were activated through mechano-chemical reactions (powered by clean electricity) rather than calcination. If complete data were available, this technology would score well across many key technological, market, and financial cost criteria.

Figure 3. Limestone calcined clay material and plant in Colombia, courtesy of Daniel Duque at Cementos Argos SA.

Figure 3. Limestone calcined clay material and plant in Colombia, courtesy of Daniel Duque at Cementos Argos SA. -

Electrochemical Process + Renewable Energy

This technology uses an electrochemical process to decompose non-carbonate rocks and industrial waste into cement at ambient temperature. This process uses electricity from renewable sources. The end product is ASTM C1157 compliant and serves as a drop-in replacement for portland cement in ready mix concrete (ASTM 2023). It offers similar performance and mechanical characteristics as portland cement (fresh and hardened properties, e.g., slump, durability, strength, set time) for buildings and infrastructure. With respect to scalability, it is currently available by the metric ton (as of 2023) with a new plant in development for additional scale-up of production. No cost information was available to evaluate the financial criteria (Sublime 2024). If complete data were available, this technology would score well across many key technological and market criteria with cost yet to be determined.

-

Calcium Silicate Rocks

This technology can be used to produce two core products used in concrete: portland cement and SCMs. Typically, cement and SCMs are made from different processes and sourced from different locations. Calcium silicate rock as the raw material source contains the minerals necessary to make both cement and SCM from one process in one location. One company, Brimstone, has developed a product that is chemically and physically identical to conventional portland cement and is starting to build a plant for production at scale. The product scores well on technological criteria and market size, but financial criteria cannot be assessed without additional information.

-

3D Printed Concrete

3D printed concrete is being used to build residential homes and commercial buildings across the U.S. For example, Los Angeles has built the first permitted structure incorporating this technology, and the construction company has promoted it for post-disaster recovery/rebuilding and lower-cost housing. The process only took about 15 months from design to completion (including permitting) because the project team leveraged their partnerships, working with municipal experts and a nonprofit clean tech incubator. The company clearly identifies and articulates the concrete technology’s value proposition, market niche, and a competitive cost and construction timeline for homes that can quickly pass building inspections, thereby offering advantageous market and financial attributes (LA Times 2023; Emergent 2024). 3D printed buildings are both fire resistant and energy efficient. Other benefits of the technology include reduced build times (by about 10%), reduced personnel needs, and reduced materials such as concrete, rebar, and exterior and interior finishes (see figure 4). The technology scores well on the technology development stage, and it scores moderately on emission reduction potential, scalability, and market size, with a delivered cost similar to BAU.

Figure 4. Emergent 3D Construction, courtesy of Don Ajamian at Emergent.

Figure 4. Emergent 3D Construction, courtesy of Don Ajamian at Emergent. -

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Sequestration (CCUS)

Many CCUS technologies inject CO2 into concrete where it converts to a permanently stored mineral, improving concrete properties. This process can be applied to a variety of markets such as ready mix concrete as well as precast concrete, masonry, and even reclaimed water. Twelve concrete companies have already adopted this technology, so carbon-sequestering concrete products have high TRLs and are scalable. For example, CarbiCrete, a Montreal-based company, uses steel byproducts instead of cement to create concrete masonry units that are cured with CO2, helping the concrete reach full strength within 24 hours (CarbiCrete 2025). This technology scores well on technology development and emission reduction and moderately on market size, with scalability and delivered cost still being assessed.

-

Ground Glass Pozzolan

Ground glass pozzolans are gaining popularity to reduce glass waste and increase sustainability in concrete materials. With glass being a non-biodegradable material, ground glass can be recycled and added to both concrete or to cement depending on the grind size (Ahmad et al. 2022). For example, glass ground to a fine aggregate size can replace up to 40% of aggregate, whereas an even finer grind of glass can replace between 10-20% of cement for optimized mechanical properties such as strength and durability (Ahmad et al. 2022, Ehrlich 2023). The emission reduction potential is moderate while its TRL is currently 7-9. This technology also scores high on market size due to ready mix applications (see figure 5) but its scalability is contingent on more efforts to focus on properly recycling and cleaning waste glass to increase its availability for use in concrete. New York cities like Syracuse and Binghamton as well as the state’s Department of Transportation have fully adopted recycled glass concrete (including a $21.2M project). For delivered cost, ground glass pozzolan/recycled glass concrete can range from equivalent to BAU to a 15% lower-cost option (KLAW 2024).

Figure 5. KLAW Industries Truck, courtesy of Jacob Kumpon at KLAW Industries.

Figure 5. KLAW Industries Truck, courtesy of Jacob Kumpon at KLAW Industries.

Commercialization Requires Both Market Supply and Demand

Wide-scale technology adoption and commercialization require actions across the market spectrum from supply to demand. We can take the concrete market as an example. For more information, please download the Implementation and Commercialization Strategy factsheet.

On the supply side, since production of concrete is largely a local enterprise, new technology adoption in this sector requires product manufacturing facilities to be established in the U.S. within local geographies. This requires establishing new plants or retrofitting old ones, training and perhaps reskilling plant employees, and developing technical assistance teams and educational materials locally. | On the demand side, the new products or technology would need to be used in construction projects. In the concrete industry, if the innovative technology works in ready mix for example, there will need to be sufficient plant infrastructure built out so that any project looking to use the material could obtain adequate supply. For precast concrete, the end product may be shipped longer distances but increasing distances adds to project budgets, timelines and fuel consumption from transportation. |

Acknowledgements

This website was made possible through the generous support of Breakthrough Energy, Conscience Bay, Energy Innovation, and Blue Horizon. The authors gratefully acknowledge external reviewers, internal reviewers, colleagues, and sponsors who supported this project. External expert reviewers included Sureka Sumanasooriya from the American Concrete Institute NEU and Reshma Singh from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. We also received support and advice from Simon Brandler of Brimstone, Daniel Duque of Cementos Argos, Don Ajamian of Emergent, Jacob Kumpon of KLAW, and Erin Glabets of Sublime. Internal reviewers included Steve Nadel, Richard Hart, and Nora Esram. External review and support do not imply affiliation or endorsement. Lastly, we would like to thank Mariel Wolfson for editorial guidance, Kate Doughty and Rob Kerns for web design support, and Ethan Taylor for his help in launching this website.

Resources

Download the Background for the Evaluation Framework

Download the Implementation and Commercialization Strategy

View our evaluation framework presentation slides here (presented at the 2024 Buildings Summer Study): www.aceee.org/proposed-evaluation-framework-new-and-emerging-low-embodied-carbon-concrete